|

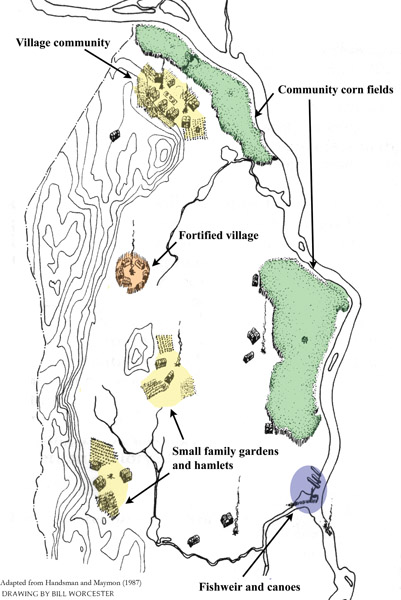

| An example of dispersed hamlet-based community organization (adapted from Handsman and Maymon (1987)) |

Southern New England has been occupied by people for at least 11,000 years. The area was first colonized by a group referred to as the Paleoindians, who entered New England shortly before the end of the last Ice Age. At that time, southern New England was covered in pine-spruce forest and was more similar to subarctic areas of Canada than modern-day Connecticut. Very few people lived in the region at this time – perhaps as few as 100 individuals in extended family camps of 30 or so. These people were likely the ancestors of all later Native groups. The Paleoindians are known to have been very mobile people. The stone materials they used often came from sources over 100 miles away from the archaeological sites at which they were found. Because so few people likely lived in the region it is unlikely that they acquired these materials through trade. Rather, they seem to have quarried them themselves during their wide-ranging annual movements. To survive, Paleoindians must have taken advantage of a variety of plant and animal resources. They probably hunted caribou and moose, as well as small animals like beaver and muskrats. They may have hunted seal along the coasts, and probably fished for salmon, perhaps even along the Quinebaug River.

About 10,000 years ago the Ice Age came to an end. However, the climate and environment did not take on its modern character until about 5,000 years ago. Archaeological sites predating 8,000 years ago are very rare across New England. Nevertheless there is some evidence that daily life was becoming more complex in eastern Connecticut. One large site recently found on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation provides evidence for the construction of relatively large houses that were dug partially into the earth. They were probably used for winter shelter. The food remains recovered there suggest a focus on wetland plant foods. Hazelnut shells indicate harvesting of this nutritious food as well. Deer, turtle, beaver and muskrat were probably also hunted or trapped. Archaeological sites dating after 8,000 years ago are much more common. During this period nearby stone quarries of quartzite were routinely used, indicating a familiarity with and reliance on more local raw materials for stone tool manufacture. At this time oak forests spread across the state and it is likely that deer, bear and turkey became more common. Small game, fish and plant foods, however, probably remained important to the diet. Elsewhere in New England relatively large camps dating to this period have been excavated. Some of these are believed to be fishing camps because they are located along waterfalls and other ideal locations to catch fish. While a variety of fish were probably caught, group fishing probably focused on anadromous fish such as salmon, shad, alewife, and lamprey eels. It was during this time that the resources of the Quinebaug River probably began to support larger local Native populations.

The hunting-and-gathering way of life continued largely unchanged until about 3,500 years ago. As the human population in the region increased, social relations between groups likely became more complex. It was around this time that a more formalized exchange of non-local goods probably began. People also began to increasingly utilize small, seedy plant resources such as goosefoot. Goosefoot is a highly nutritious, but difficult-to-gather plant food. Its use suggests that local populations had more limited access to other, more easily gathered and processed resources. In short, Native communities were beginning to become more concentrated on the landscape, thereby reducing opportunities to move and access the same variety of resources they once enjoyed.

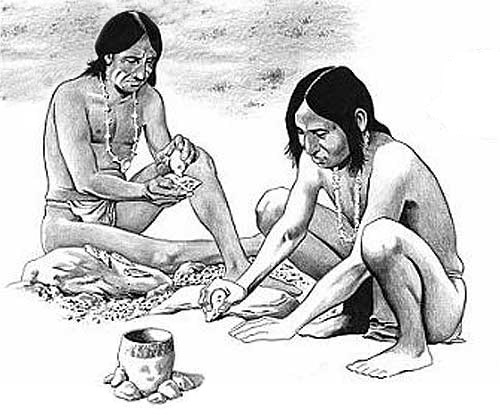

|

| Artistic recreation of food processing activities |

After 3,000 years ago, pottery was increasingly used by Native people in the region, replacing bulky soapstone bowls and platters. It was about this time that evidence for the intensive use of shellfish also increases. To some researchers, the use of pottery to process foods and the introduction of shellfish to the diet are indicators of population stress and reduced foraging territories. Large underground storage features are more common at sites after this time as well, suggesting increased efforts to hoard and preserve food for lean months. There is some evidence that hickory nuts and even acorns (which require substantial processing for safe human consumption) became an increasingly important part of the diet. In general, the archaeological record suggests an intensification in the use of wild plant foods. This might have even resulted in the first experiments with small-scale gardening (horticulture) of some native plant species.

The Native American way of life we are most familiar with in New England, based on the planting of maize, beans and squash (the Three Sisters), developed only about 1,000 years ago. The transition to a gardening way of life appears to have been very gradual. By about 1300 A.D., some communities along the Connecticut River Valley probably developed village-based communities associated with large fields of corn. The archaeological evidence along the Connecticut coast, however, suggests that gardening never became very important. These communities continued to follow a largely hunting-and-gathering way of life focused largely on a rich marine food base, perhaps supplemented by small family gardens. In the eastern and western uplands of Connecticut, where the growing season is shorter than it is in the central Connecticut River Valley, relatively small hamlet-based communities probably also planted family gardens to supplement their hunting-and-gathering way of life. Only during periods of political upheaval would such groups likely have formed larger, village-based communities. No large Native American village sites have been found in the Quinebaug River Valley, but only a small amount of archaeological work has been done in the region, so their presence cannot be ruled out.

References: Handsman, R., and J. Maymon (1987) The Weantinoge Site and an Archaeology of Ten Centuries of Native History. Artifacts 15(4):4-11.